Greg Hoch’s article on page seven of the June/July issue of American Waterfowler, “Routes That Were, And Are,” unleashed in me a flood of memories of time and place and birds.

I have a daughter, now mostly grown, who is a sensitive soul. When she was very young, she would melt down in tears of anguish over events no one could control like the loss of an aged, great uncle she barely knew, the passing of an old, neighborhood dog that was far too long for this world or a favorite neighbor moving away. I would tell her, “Honey, everything changes. That is the nature of this world. Nothing stays the same forever.” But bless her heart, these were, to her, incomprehensibly sad events.

And so perhaps it is, as we go through life and witness those things that stir our hearts, that we seldom stop to think, “I may never see this here again.”

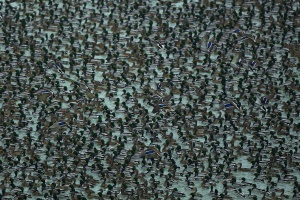

I think about the bluebills that once rafted on the vast waters of Lake of the Woods. How we used to hunt them every deer opener because we knew the bays they liked to feed upon would be free of hunters and we’d have the good gunning to ourselves. How one November, while working on a book project and seeking photos, I hired a float plane whose ancie nt pilot coaxed the slow-moving yellow bird out over the vast lake until we were looking down at a rolling mass of black dots—a vast, living carpet of bluebills, some 600,000 strong.

nt pilot coaxed the slow-moving yellow bird out over the vast lake until we were looking down at a rolling mass of black dots—a vast, living carpet of bluebills, some 600,000 strong.

Everything changes. Today there is no “great raft” on Lake of the Woods, and there are no great migrations of that many birds through the Minnesota lake country—an event similar to a five-alarm fire that lasted one or two weeks for the many duck hunters who answered the bell. The bluebills moved west, apparently, to the ever-growing body of water called Devil’s Lake, where freshwater shrimp thrive (no doubt the shrimp are more dependable than cyclical rice crops). Lesser scaup also suffered a mysterious decline continent-wide, their overall numbers now just one-third what they were three decades ago.

And what of the snow geese that used to blanket North Dakota in the fall? Flocks once so thick, so enormous in size that a hunter did not need decoys to enjoy a morning’s pass shooting. Those that had the moxie to decoy the birds did even better. But the birds were pushed and prodded from sunup to sundown and apparently grew tired of the game. Up in Bottineau County, the Bottineau shootout raised money for Ducks Unlimited as teams of snow goose hunters came from long distances to participate. But that died too. Now only a smattering of the vast white flocks stop in North Dakota in the fall.

Yep, everything changes. Fortunately for us as waterfowlers, when one door closes, another seems to open—somewhere. Aside from the anomalies, duck production has been good in the past decade. Canada geese have never been stronger, and snow geese, though fickle as ever, continue to take up a lot of space. The traditions of ducks and geese have changed with the landscape, and hunters will continue to adapt. As sad as the passing of waterfowl traditions are, nothing stays the same forever. It’s the nature of this world.